By Emily Margosian, assistant editor

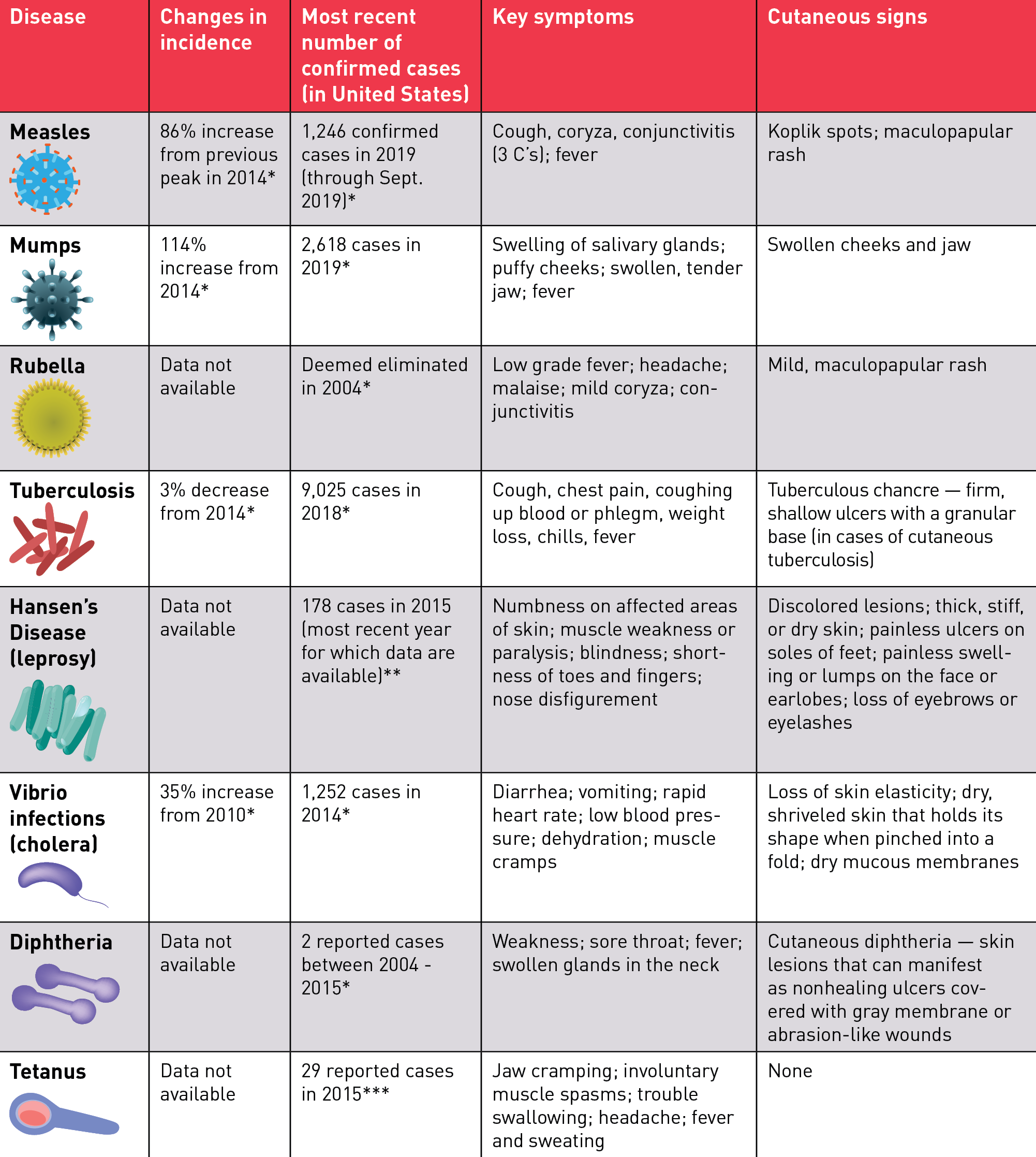

“Fifty years ago, many people believed the age-old battle of humans against infectious disease was virtually over, with humankind the winners,” writes the 2007 NIH’s Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. “The events of the past two decades have shown the foolhardiness of that position.” While historically humankind has grappled with the devastating effects of infectious disease — bubonic plague, cholera, Spanish flu — deaths have significantly declined over the centuries due to improvements in living conditions and medical care. However, the past several years have revealed a disturbing trend, as infectious diseases have begun to re-emerge at “an unprecedented rate,” according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Among those returning are measles, mumps, tuberculosis, and other “classic” diseases previously considered to be near eradicated in the developed world. So why have these past pestilences returned?

While evolving environmental factors have been linked to the emergence of many “new” infectious diseases, the re-emergence of the so-called classics can be attributed in part to cultural shifts and changing patterns of human behavior. This month, Dermatology World explores the cultural factors at play in infectious disease re-emergence, and what symptoms dermatologists should look for in their own patient populations.

Lower vaccination rates

Ask any health care professional to name the number one driver of re-emerging infectious disease, and their answer is overwhelmingly likely to be vaccine non-compliance. The anti-vaccination (“Anti-vaxx”) movement has been building in the United States for decades, and its birth is generally linked to a since-discredited Lancet study associating the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine with autism. Despite robust scientific support for vaccination, the movement has continued to thrive, fueled in part by “an internet humming with rumors and misinformation; the backlash against Big Pharma; an infatuation with celebrities that gives special credence to the anti-immunization statements from actors like Jenny McCarthy, Jim Carrey, and Alicia Silverstone,” according to a 2019 New York Times feature.

Although five states — New York, California, Maine, Mississippi, and West Virginia — have eliminated vaccine exemptions for religious and philosophical reasons, the effects of decreased vaccination rates have begun to take a toll on public health. “When some groups decline vaccination, it decreases herd immunity and creates a reservoir of disease,” said Dirk Elston, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology and dermatologic surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Additionally, some research indicates that the body can develop “immune amnesia.” “Two studies of blood from unvaccinated Dutch children who contracted measles now reveal how such infections can also compromise the immune system for months or years afterward, causing the body to ‘forget’ immunity it had developed to other pathogens in the past” (Science. 366: 560-561; Nov.1, 2019).

The resurgence of measles in the United States is often linked to the anti-vaccine movement. Easily preventable with two doses of a safe and effective vaccine, in 2016 the estimated number of global deaths from measles fell to 89,780 — the first time in history that annual deaths had fallen below 100,000 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2019; 19(4): 362-363). Since then, however, the disease has experienced a worldwide resurgence, even among developed nations where measles had been previously declared eliminated. While the re-emergence of measles at the global level can be ascribed to multiple factors, such as conflict and lack of access to health care resources, the return of measles to the developed world has been primarily attributed to vaccine hesitancy.

A resurgence in one vaccine-preventable disease portends future vulnerability to outbreaks of other infectious diseases, suggests Kate O’Brien, MD, MPH, director of the WHO’s Department of Immunisation, Vaccines, and Biologicals. “When you have a resurgence of measles, it’s an indication that we’re backsliding on other vaccine targets. The same children that are getting measles are exactly the same children who are poorly immunised against polio, diphtheria, and pertussis,” she explained in a 2019 Lancet article (19(4): 362-363).

Stephen Tyring, MD, PhD, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, agrees that dermatologists should keep their eyes out for more than just measles. “Physicians should also be aware of potential cases of mumps and rubella, which are prevented by the same vaccine used for measles — MMR.”

Although the anti-vaccine movement is primarily rooted in the United States, subsequent vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in other countries suggest that the trend has begun to spread globally. “I believe the U.S. and European anti-vaccine movement will begin extending into Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where we are already seeing anti-vaccine activities in the Philippines,” said Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, vaccine scientist and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, who has advocated for government action to prevent the spread of vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories on social media, in addition to mounting comprehensive pro-vaccine advocacy campaigns (Lancet Infect Dis. 2019; 19(4): 362-363).

Dr. Tyring advises that dermatologists remind their patients to seek vaccination against diseases to which they may be susceptible. “We need to educate patients that vaccines are at least a million times safer than the diseases that they prevent,” he said. “Patients should also be reminded to contact their physicians if they suspect an infection, and both patients and employees should be encouraged to obtain the annual influenza vaccination.” Dr. Elston adds that dermatologists can play a key role in public health efforts to control infectious disease outbreaks. “We are often the first to see and diagnose vector-borne and other diseases and report them to public health authorities,” he said.