By Ruth Carol, contributing writer

You either signed one when you joined a practice, or you had dermatologists sign one when they joined your practice. If you sell that practice one day, you will likely sign two. Non-compete clauses are a standard part of employment and transaction contracts but navigating the nuances of them can make all the difference in where you practice next.

Non-compete defined

A non-compete clause precludes a physician from engaging in competition with an entity (i.e., a practice, clinic, hospital) for a period of time in a particular geographic location after leaving the entity, explained Rob Portman, JD, who serves as legal counsel for the AAD/A. The purpose of signing a non-compete is to ensure that the physician doesn’t open an office nearby and directly compete with his or her former employer, he added.

Non-complete clauses always have a duration and geographic scope, both of which must be reasonable. A reasonable duration is considered anywhere from one to three years. If it’s longer than that, the employer would have to make a strong case as to why a longer duration is necessary to protect the investment it made in the physician, said Daniel F. Shay, Esq., an attorney with Alice G. Gosfield and Associates in Philadelphia. “At some point, it can become about punishing,” he said. “Courts don’t favor punishment or indentured servitude by locking you into your job.”

Regarding geography, the assumption is that patients cluster in certain areas, said Portman, who is a health law and nonprofit attorney with Powers Pyles Sutter and Verville PC in Washington, D.C. Outside of that five- or 10-mile circle, it’s less likely that patients would want to continue seeing the same physician because it’s inconvenient. A larger geographic scope has less impact if it’s around a rural location because there are fewer practices nearby versus an urban location, which could have a several practices within close proximity.

Regarding practice type, non-competes usually refer to services consistent with a full-service dermatology practice. However, if the dermatologist plans to practice pediatric dermatology or Mohs surgery, services not offered by their current employer, the dermatologist could make the case that there is no competition. “You’re not in competition if the employer doesn’t provide the services you intend to offer,” Shay said.

Typically, non-competes come with a non-disclosure and non-solicitation clause, all under the rubric of restrictive covenants, Portman explained. A non-disclosure clause may include language about confidentiality and trade secrets. A non-solicitation clause prohibits the physician from soliciting patients and employees whether the new employer is across the street or across town. The non-solicitation clause could be binding for a year or more, depending on what is written in the contract. It’s important to define “solicitation,” said Richard Cooper, a health care attorney with McDonald Hopkins in Cleveland. If the physician doesn’t directly solicit former patients, but the new group they join does as part of a normal marketing process such as a mass mailing, is that considered solicitation?

Consequences

Consequences of signing a non-complete clause can vary. The dermatologist is giving up some of their freedom to choose where to practice next for a certain period of time, Cooper said. Some non-competes are so broad that the dermatologist may have to move to a different state to practice, although non-competes with geographic restrictions that are too broad risk non-enforcement. On the other hand, if the physician is moving across town or to a different city, then the non-compete is likely to be inconsequential, Portman said. In the event of a sale, however, a non-compete may prevent the former owners of the practice from continuing to practice dermatology anywhere in the area, he added.

Physicians who violate a non-compete clause can find themselves hit with an injunction and hefty legal fees for themselves and the enforcing party. Most non-competes indicate that the employer can go to court for a violation and obtain injunctive relief, Portman said. “Going to court is expensive, time-consuming, and soul crushing,” Shay added.

The former employer can seek a preliminary injunction, requiring the dermatologist to stop practicing immediately, said Daniel Bernick, JD, MBA, vice president of the health care law section and president of health care consulting at The Health Care Group in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania. Preliminary injunctions are heard by the court on an urgent basis because of the immediate harm caused to the former employer by the dermatologist’s new employment. Most physicians on the wrong end of an injunction comply with the court order because not doing so could land them in jail, he said. Often, a preliminary injunction ends the case, because the dermatologist does not want to incur further attorney’s fees and be forced to pay damages to the plaintiff too. Defending a lawsuit like this is always expensive and can be prohibitive for physicians who are trying to start a practice and must sign leases, buy equipment, and hire staff — all while facing the risk that their entire operation could be shut down.

State laws vary

The consequences of violating a non-compete clause can be stiff, but they are always subject to judicial review if one of the parties believes the non-compete is unreasonable, Portman said. In a contractual dispute, the courts decide what is reasonable.

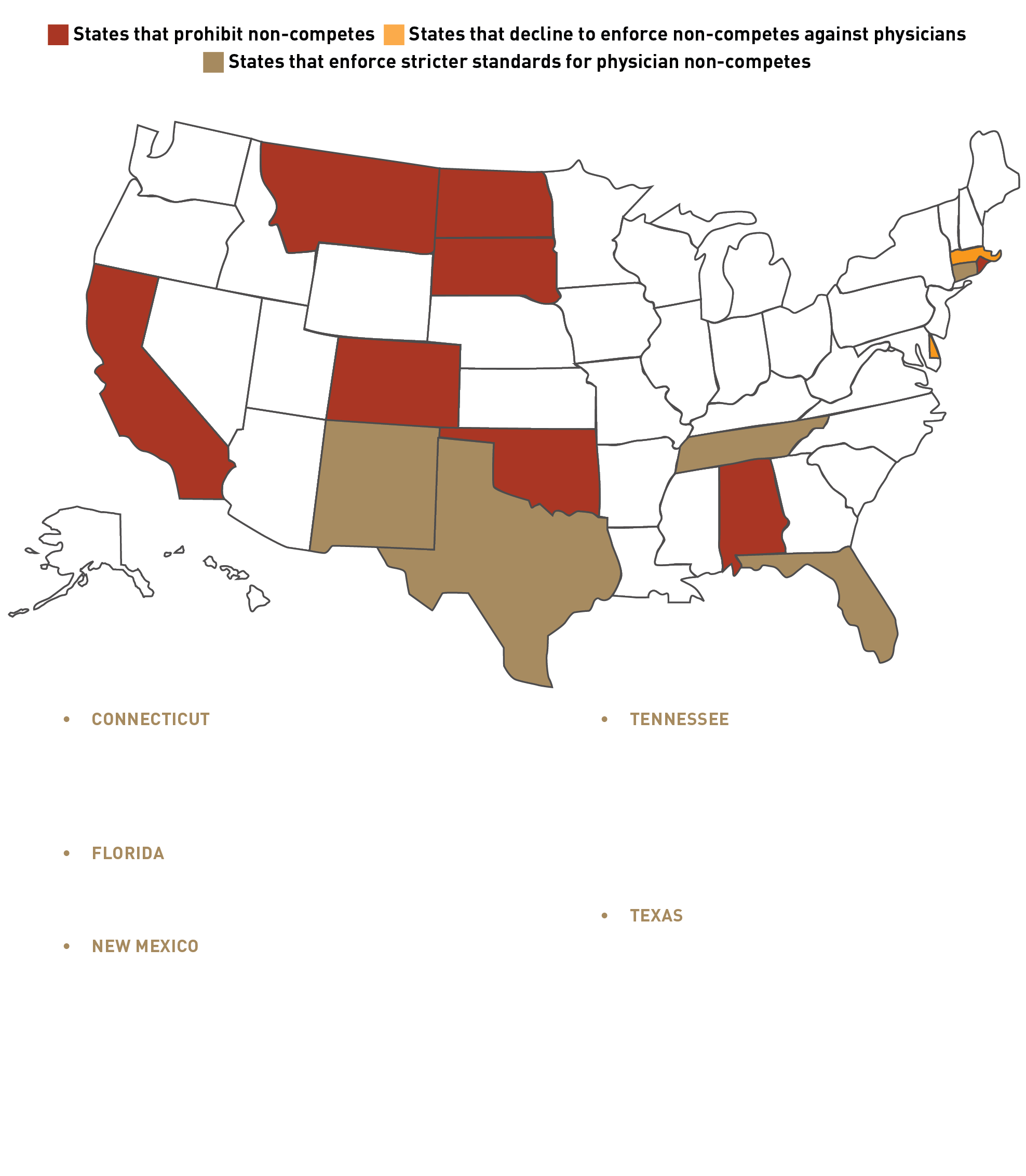

In recent years, however, the courts have been less supportive of non-competes, Bernick said. Nearly 30 states have introduced bills to modify their non-compete laws. (See sidebar for details.)

Most states address non-compete clauses through common law, which can change over time, Shay said. A key court consideration is whether the non-compete will have a harmful impact on the public. If the non-compete prohibits the only Mohs surgeon in the region to practice, for example, it will likely not be enforced, Bernick stated, because it could put the health of the patient population at risk. In 2018, Colorado amended its non-compete law to allow a physician to disclose their intent to continue practicing and provide new professional contact information to their patients who have a rare disorder. The statute relies on the National Organization for Rare Disorders’ database to determine which diseases are considered rare.

Some, but not all, states permit the judge to rewrite the non-compete clause instead of throwing it out in its entirety, Cooper said. The judge can reduce the restrictions, whether they relate to geographic location or duration, to restrictions with which the judge is comfortable. For example, he has seen “tiered territory definitions” that go from “within 20 miles of the practice site…but if 20 miles isn’t enforceable, within 10 miles of the practice site,” and so on. These pre-drafted definitions make the judge’s job easier, he added.